|

Image

taken from Cubarte, website of the Ministry of Culture of the Republic

of Cuba, on 26 April 2010. “Tomb of the seamstress of the Cuban Flag

found”, in Prensa Latina (Matanzas), News section, at

www.cubarte.cult. cu

The

history of the Americas has many examples of cultures, especially

Cuba’s, that have woven new identities, as with the United States, and

continuing in the 19th century and into the 20th.

It is no

surprise that the Cuban flag was conceived on U.S. soil in 1849 and from

there went to Cuba. These pages are dedicated to unraveling those

details, and take as their main sources (among others) the first

historian of Havana, Emilio Roig de Leuchsenring (1889–1964)

and, basically, his Banderas oficiales y revolucionarias de Cuba

[Official and Revolutionary Flags of Cuba] (Colección Histórica Cubana y

Americana 7, Municipio de La Habana, 1950, 143 pages), “Homenaje del

municipio de La Habanaa nuestra enseña nacional en su primer

centenario, 1850–19 de Mayo de 1950” [“Tribute from the municipality of

Havana to our nation’s flag in its centenary, 1850 to 19 May 1950”]),

and his Cuba y los Estados Unidos de América: Historia documentada de

la actitud disímil del Estado y el pueblo norteamericanos en relación

con la independencia de Cuba, 1805–1898 [Cuba and the United States of

America: The Documented History of the Dissimilar Attitudes of the

North American Government and its People Regarding the Independence

of Cuba, 1805–1898] (“Publicaciones de la Sociedad Cubana de

Estudios Históricos e Internacionales”, La Habana, 1949; 279 pages, 21

cm).

Other

sources were also very revealing, especially in the José Marti National

Library and the Ruben Martinez Villena Central Library at the

University of Havana: Emeterio Santiago Santovenia y Echaide

(1899–1968), in his article on La bandera de Narciso López en el Senado

de Cuba [The Flag of Narciso López in the Senate of Cuba] (Havana,

Senate Official Editions, 1945, 47 pages, 18 cm), and above all,

Dr. Herminio Portell Vilá (born 1901, Professor of American

History at the University of Havana and of Cuban Military History at the

War College, considered the definitive biographer of Narciso López, to

whom we owe the Cuban flag), with his Breve biografía de Narciso López

[Brief Biography of Narciso López] (Sociedad Colombista Panamericana,

1950) and Narciso López y su época [Narciso López and his Times]

(Compañía Editora de Libros y Folletos, Havana, 1952), as well as

Ezequiel García‐Enseñat’s

Estudio de las banderas de Cuba [Study of the Flags of Cuba].

Although

Roig’s history goes back to when Spain claimed Cuba under the

flag of Castile (allegedly purple but more likely crimson), of

particular interest is his inquiry into the flag used when Cuba joined

the roll of nations in 1902 after its independence in 1898. That flag

had been conceived by Narciso López, a Venezuelan born in Caracas on 29

October 1797: we note that it was created and developed during the era

in which Latin American independence flourished, and that among the

dreams of López’s countryman, the liberator Simón Bolívar, Cuba

was never forgotten.

Son of an

established merchant and landowner in Valencia and Caracas, and of a

lady from an old and distinguished Caracas family, López received

in Caracas an education equal to or greater than that of many

leaders of the Venezuelan independence, although not as much as that of

Bolívar, who had the best private tutors. López studied at the

Wantosten Academy of Mathematics, created by the country’s supreme

governing board. When its students, after Venezuela’s declaration

of independence of on 5 July 1811, petitioned the military commander of

Caracas for military training in service of the country’s independence

struggle, among the signatories was 13‐year‐old

Narciso López. He was not called, presumably because of his young age

(Portell, 1952:4–5).

By the

time López was 16, he was trying to join the fight against Spanish

colonialism. Despite his abilities, he was not accepted by the

liberators (perhaps because of a strongly anti‐independence

uncle, which led the patriots to distrust him), still he felt

the call to fight for Venezuelan independence. According to Portell

(1952:5–6), López was among the besiegers (“but as a spectator”) when

Bolívar besieged Puerto Cabello, in September 1813, and shortly

afterwards along with Bolívar, he watched the Spanish reinforcements

arrive, and in September he was part of the triumph of General José

Félix Ribas at La Guaira (“but without fighting”)… without actually

joining the independence fighters. He finally acceded to the insistence

of his uncle and became a Spanish soldier—the same day that

Simón Bolívar was defeated in the disaster of La Puerta, which

seemed to be the end of the independence movement, by Boves and his

rangers (who, in taking Valencia, killed López’s father).

López came under the protection of one of the most unscrupulous but

brave lieutenants of Boves, who exercised an unfortunate influence on

him. He rose in the Spanish army without wanting to spill the blood of

Venezuelans, wearing he would call “that brilliant but ignominious

livery”.

In 1819

López was a lieutenant colonel and distinguished himself in

the Battle of Carabobo, which led to his promotion to

colonel. He was governor of Maracaibo (the last Spanish

stronghold) and second in command of the Spanish army when,

after the triumph of the Venezuelan Independence in 1823, it

evacuated to Santiago de Cuba. At that time Cuba was shaken by the

Conspiracy of the Suns and Rays of Bolívar (a Masonic group

plotting Cuban independence) and the possible invasion by Paez under

orders of the liberator Bolívar, while the annexation movement was

beginning in Cuba. Some of his countrymen would later join him in his

revolutionary efforts.

López

married the sister of a Havana man who would become Count of Pozos

Dulces. When he appeared with them in a trial regarding the

landholdings of the family in El Vedado, showing contempt of court by

refusing to appear in full uniform of a colonel of Hussars of Fernando

VII, this attracted the attention of Cubans seeking a gifted and

resolute military leader, in spite of his service to Spain and its

reprehensible representatives. But in the first months of 1827 he was

sent to Spain without a command, the Spanish fearing that he was

sympathizing with the Cubans (such as the conspiracy of the Black

Eagle), as well as with other officers defeated in America, who were

called Ayacuchos after the great defeat of Spain in Peru. He did in

fact connect with the Ayacuchos and Creole residents in Cuba, joining

the Club de La Habana (Club of Havana).

At the

beginning of the Carlist war in Spain, López was recalled to active duty

and would save the life of his general Jerónimo Valdes, who assigned him

to the international commission to regulate the Carlist War and

eliminate the atrocities by both sides, and won the praise of his

English colleagues. He was liberal and progressive, and came to be

among the most influential reformers, winning high military degrees and

defeating Colonel Carlos O’Donnell, earning the undying hatred of

his relative, Leopold O’Donnell. When in 1836 the Cuban

deputies were expelled from the Spanish Court, he called on

all Creole officials to resign en masse and promoted protests

by the Club de La Habana, made personal entreaties to the

Spanish legislators, and obtained the support of General Valdes,

although in vain. He was associated with in the conspiracy in Spain of

the Triangular Chain and Suns of Freedom (based in Havana but with

branches in Spain) and was betrayed; his ideological evolution toward

the revolution is explained by living within the monarchy to its service

and meet its ills from within.

In Spain,

López (first in Barcelona, then Madrid) contributed significantly to the

downfall of the regency of Maria Cristina (1840) and the establishment

of the regency of Espartero, which was considered a victory for progress

(Portell, 1950). It was López who, as military governor of the plaza,

received Espartero on his arrival at the Court of Madrid, and

his liberal friends were placed in positions of power ... until

Espartero fell. Meanwhile, he had sent to Cuba for his elderly mother

and his niece, Mrs. Rosa Salicrup de Sanchez; another relative of his

(Manuel Muñoz de Castro) was the consul of Venezuela in Havana.

Cuba had

rebelled against the “scandalous closure of the Courts to the

representatives of Cuba and Puerto Rico” and wanted to “free both

islands from the clutches of his equally ruthless greedy stepmother”

(Roig, 1950) and the United States tried to buy Cuba from

Spain. And when the new governor of Cuba, Leopoldo O’Donnell, the

mortal enemy of López, arrived in Havana in March 1843, he stripped

López of his high office and forced him to leave the military, sowing

the seeds of rebellion on already fertile ground. López

would be involved in the Conspiracy of La Mina de la Rosa

Cubana (1847, named after one of the wells of the San Fernanda

mining reserve in Manicaragua) in Las Villas.

Three

flag designs for Cuba appeared in this era. The first, according to a

letter from Cirilo Villaverde to the director of La Revolución de Cuba

(15 February 1873), used the Republican colors in horizontal stripes:

blue, white, and red, in a distant imitation of the flag of Colombia.

The second, according to José Sanchez Iznaga on 10 July, had

a large star at the hoist from which ran three equal stripes of

blue‐white‐blue;

a variant of this flag has a red star at hoist end of the central white

stripe, and is shown this way on the shield used on the proclamations of

Narciso López in 1850 and described by Dr. Portell in his Historia de

Cuba en sus relaciones con los Estados Unidos y España [History of Cuba

in its Relations with the United States and Spain] (1938). The third,

designed by members of the Club de La Habana and published by Enrique

Gay‐Calbó

(born in Holguín, 1889) in his La bandera, el escudo y el himno [The

Flag, the Coat of Arms, and the Anthem] (Havana, 1945), had a blue

rectangle at the hoist, with an eight‐pointed

white star and three wide red stripes separated by two narrow white

stripes (according to the design in the files of Dr. Portell).

Meanwhile, López met with the United States consul in Havana, Robert B.

Campbell, through whom he learned that in Havana there was another

conspiracy—but this one annexationist— headed by landowners and rich

Creoles such of those in the Club de La Habana. When this plot failed,

López managed to escape disguised as a sailor on the Neptune, sailing

out of Matanzas bound for Newport, Rhode Island, in the United States,

while in Cuba, the Spanish government in 1849 sentenced him in

absentia to death by firing squad. Cuban émigrés had different

opinions—some were against annexation, including those who rejected U.S.

support, and some were for annexation, both those who preferred the

slave‐owning

South and those who favored the democracy of the North. People in

United States also differed in their views and goals in weaning Cuba

from Spain—Southerners wanted to turn Cuba into another slave state and

were applauded by Cuban slave‐owners,

while Northerners wanted to annex Cuba and free its slaves, and

introduce other liberties. These same differences, just fifteen years

later, would lead to the United States into a civil war to

abolish slavery and establish a new order in the northern

colossus, which would also defeat the annexation aspirations of the

Cuban slaveholders. But in 1850, this future was still unknown.

At that

time a traditional and healthy relationship had long existed

between the peoples of Cuba and the United States, from the very

beginnings of both nationalities. Not surprisingly, among North

Americans who have risked their lives for the freedom of Cuba, one of

the most important fighters was Henry Reeves, called “the Little

Englishman”. In the same way, many Cubans have fought for the just

causes of the people of the U.S., among then, the Havana‐born

José Agustín Quintero y Woodville (1829–1885), who was imprisoned in

1848 (with Villaverde and others) and sentenced to death, but escaped to

the United States to fight in the Civil War with the republican North

against the slave South, and then to fight with Juarez in Mexico. It is

no coincidence that in Portell’s vast work can be found, for example,

the biography of Reeves and Los Cubanos y la Independencia de EUA

[Cubans and the Independence of the United States], (1946).

Furthermore, the United States has traditionally long been a

refuge for persecuted and disgruntled Cubans, and the influences

between the two peoples are many and deeper over time; Cuba’s flag flies

atop such influences.

Roig

quotes Gerardo Castellanos (p. 139), who analyzed the efforts of López

to get all possible support (even that of annexationists) for his

campaigns in Cuba; he led U.S. Southerners to believe that Cuba

would continue slavery, and at the same time he flattered the

Northerners about their freedoms, attracting politicians and

businessmen, offering to pay veterans (including Robert E. Lee,

who would become the Confederacy’s best‐known

general, and Jefferson Davis, who would become its president) to

participate. For this he would be widely criticized as an

annexationist by Cuban independence leaders; Dr. Portell

counters this by pointing to the lone star (for full independence) on

the flag. However, even in 1888 Manuel de la Cruz (1861–1896), of

Havana, accused López of sympathizing with annexation, which led to a

famous controversy with Cirilo Villaverde.

Upon

arriving in the United States, López joined with others seeking Cuban

independence to create the Junta Promovedora de los Intereses Políticos

de Cuba [Board for the Promotion of the Political Interests of Cuba, or

the Cuban Junta of the U.S.], a splinter group opposed to the

annexation goals of Cristóbal Madan, and made contact with the

plotters of the Club de La Habana, which used a very different flag

from that which López would design. The propaganda organs of the Cuban

Junta of the U.S. were the newspapers La Verdad [The Truth] (New York),

and La Patria [The Nation] and El Independiente [The

Independent] (New Orleans). They negotiated with politicians and other

figures of influence, sought official government support, began

recruiting, and set up a camp on Cat Island (in the Gulf of Pascagoula,

in the Bahamas).

There

they managed in early 1849 to gather some 200 men for an expedition to

Cuba. But the sympathy of many sincere North Americans supporting a free

Cuba was not matched by the federal government, which had other

interests; the expedition to Cuba was denounced by the Spanish

governor of the island, the Count of Alcoy, and the

government in Washington demanded that López immediately disband the

expedition. Similarly, in 1849 the government under President Taylor

would demand that he disband his next expedition, organized in

Isla Redonda (Round Island).

One of

General López’s fellow strugglers in exile, the eminent novelist from

Pinar del Rio, Cirilo Villaverde (1812–1894), would relate in 1873 on

page 3 (backside) of his handwritten notebook Reseña biográfica del

general Narciso López [Biographical Overview of General Narciso López]

(held by Dr. Portell, and reproduced by Gay‐Calbó

as an appendix to his cited work), that today’s Cuban flag was

designed by López in 1849, while he lived at the home of Mrs. Clara

Lewis, 39 Howard Street, near the corner of Broadway in New

York. From that house he frequently visited the home of the patriot

from Matanzas, Miguel Teurbe Tolón y de la Guardia (1820–1857), whom

López asked to design the national arms for an independent

Cuba. Beginning in 1849 proclamations and bonds bear those arms, and

they were seen in New York, for example in a tobacconists’ shop

(Portell, 1952:138). These are Cuba’s primary national symbols,

whose roots, as is logical and obvious, are inextricably linked. In

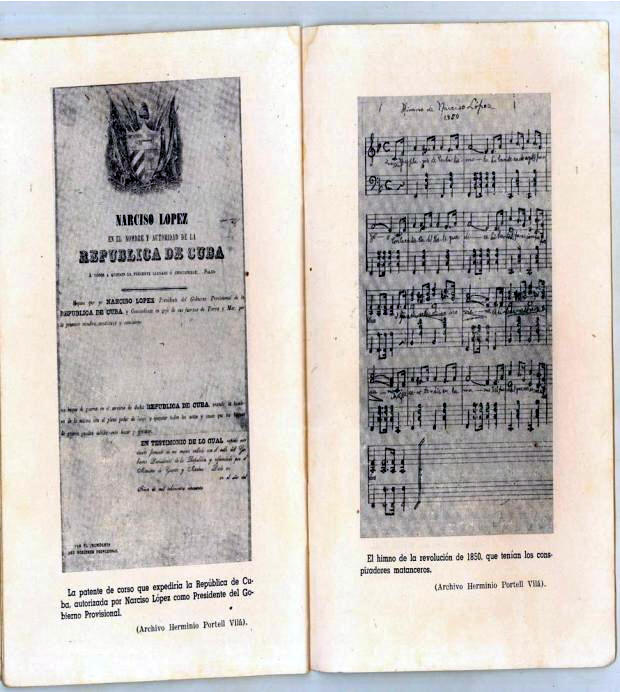

this revolutionary atmosphere it was no accident that there would even

exist a “hymn of the revolution” among the conspirators of Matanzas,

and a code with which López would communicate with other

revolutionaries underground in Cuba (Portell, 1950:33 and 35)(see

Appendices 2 & 3).

|